My mom’s mother was strong and smart, a beautiful lady with thick hair and lavender eyes. She didn’t get to go to college but had really wanted to. Her husband died during the depression, when my mom was two. She spent her life selling corsets out of her home to support her two children –my mom and her older sister– and to make sure they both went to college.

In high school, my parents knew each other in Latin class and on the debate team, where my mother mortified herself during an important competition by drawing a blank and saying, “I have nothing to say.” My dad took my mom to the ten cent movies a few times before he was drafted at 18 for WWII, and they faithfully exchanged letters for four years, with apparently plenty to say.

While he was giving X-rays in the Atlantic, my mom went to art school at the University of Michigan. She loved to dance the jitterbug and was one of four chosen to dance on the stage of Hill Auditorium during the enormous college-wide pep rallies.

She was somewhat in the shadow of her older sister, who was not only brilliant but was one of the first female students at the U of M law school, and who even turned down future President Gerald Ford’s hand in marriage.

My parents, on the other hand, got married at their first opportunity. When they were newlyweds, they got a waffle iron as a present, and their finances were so tight that the first year they ate waffles almost every night for dinner.

My mom put my father through medical school by being an art teacher. She had a different high-quality lesson plan for every grade in three elementary schools, all designed to dovetail with whatever each individual classroom was studying.

Once, while she was carpooling with several other women on their way to teach, she was in a car accident, and the package of razorblades she was bringing for her students to carve sculptures with, opened and flew everywhere, all around the car as it rolled. By some miracle, no one was hurt; she never ceased to be amazed by that.

While my Dad was studying for medical school, he said my mom’s knitting needles where too loud and distracting. My mother responded by spending months of their time together carefully oil painting the view out their apartment window of the rather dismal alley. It is her only painting that is not bright and cheery, but they were both fond of it anyway, remembering the supportive quietness of those brushstrokes.

After seven years of marriage and teaching, when she quit her job to have us, the school system had to hire three art teachers to replace my mom.

I have very vivid early memories of sitting behind my mother on the cool, black linoleum basement floor while she sewed. I was busy cutting paper, gluing, coloring, and utilizing stuff from a bottom drawer full of extra miscellaneous art supplies, which were placed there expressly to intrigue and occupy me.

On trips with her to fabric shops, ideas flowed; she made most of our clothes. I grew up choosing fabric and patterns, which she’d whirl up into being in no time. I didn’t have much store-bought clothing until the end of high school. She also made me a life-sized Raggedy Ann, which was a challenge to do, all tangled up as she was in those long stripped legs while sewing on the face with the triangle embroidered eyes.

My mother could knit complicated Fair Isle sweater patterns with multiple colors– even in the dark while at the movies– which is an astonishing feat I still can’t figure out. And I remember her bringing us a picnic to eat during the intermission of Gone with the Wind, since it was “so long.”

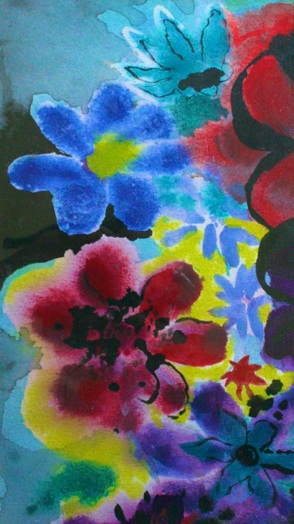

She was an avid gardener of flowers, a magician at making things grow, bringing forth beauty, and combining color. Her peonies were especially glorious. I used to take big bouquets of them to my teachers at the end of the school year, overcome by the heady fragrance every step to school. The smell of peonies still zips me back to my mother’s world in a heartbeat. I even have some of hers growing in my own yard now (see top photo).

She also loved orchids and usually had orchids blooming. Because of those majestic blossoms, my parents installed three bay windows in their ranch style home.

Hyper organized on long camping trips to national parks, my mother would pull out new books for me from their hiding place under the driver’s seat– just before I was about to lose it– and she’d awe me all over again with her thoughtfulness by anticipating my needs in advance.

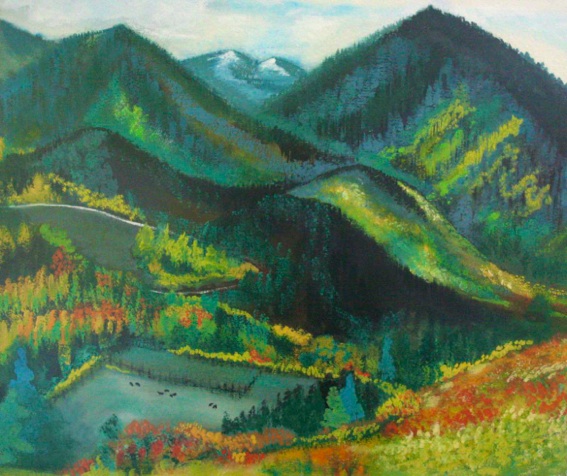

My favorite memories of these extended western trips was painting next to her the gorgeous natural scenery before us (particularly mountains) in her good chalk pastels which she freely shared with me as a kid. These moments were our mutual sanctuary, our church. It was like we breathed as one, fused with each other, the landscape, all being, and creation itself. Everything else in the whole world fell away when we did that, and I have no idea now where my father and older sisters were during those times.

At the national park campgrounds during the 60’s and 70’s, my mother liked to try to figure out if fellow campers were married or not. She would crane her neck and go out of her way to try to detect the presence of those telltale wedding rings or the lack of them. We would collude to help her in this pastime, as her little spies.

Not hearing well enough to eavesdrop, she was an avid people watcher, fabulous at picking up subtle visual cues that eluded everyone else. She could also say volumes with her eyes and facial expressions, without uttering a word.

When we visited the southwest, my mother would look closely at the Native Americans, because she felt they looked like her. She was darker than her fair mother; her real estate developer father was said to be Spanish, but they didn’t know much about his lineage. My mother became convinced that there was American Indian blood in her heritage, just by looking at indigenous peoples and feeling an irrationally powerful bond with them. This was especially interesting since she had married my father who was a lateral descendant of General Custer.

My mother was an indefatigable Girl Scout leader for nine years. As the youngest of her three daughters, I was along for the three years of junior scouts, three consecutive times. She was tireless in engaging young people with great ideas. After twenty-five years of volunteering for the Girls Scouts they gave her a bouquet of silver dollars that my mom used to plant a redbud tree in her front yard.

One year, when my sister and I went to camp, as a surprise our mother totally painted and redid our room while we were gone. I shared a room with my middle sister, and she liked green, but I liked orange. So what color did my mom paint our room? Half of each with green gingham curtains on my sister’s side and orange gingham curtains on mine. It worked remarkably well and we both liked it. As a parent now, however, I see what a risk she took in doing this.

My mother enjoyed embracing holidays with vigor. When she went shopping, things used to “jump out at her” to buy for people as gifts. Holidays seemed to unleash her generosity of spirit and give air to her creative juices.

She did Santa and the Easter bunny so well I was crushed when I found out it was a ruse, and proceeded not to do it for my own children. We left cookies for Santa, but the Easter bunny was especially clever, leaving a string tied to the end of our beds that we had to follow over and under things until we found where it led at last to our baskets. One of us always found ours hidden in the clothes dryer, a routinely reliable hiding place.

My mother made homemade Christmas cards every year, and each year’s was unique, while sporting that year’s family portrait. She made a huge banner she’d put up on the wall at Christmas-time with one card of hers from each year, a family record styled in mind-blowing creativity.

She strove to treat us all equally, to the extent that when as a young adult I asked for a paper-cutter for Christmas, she got one for each of my siblings as well, whether they wanted one or not.

My mom’s sister would often give her books on Kandinsky for Christmas, which exasperated my mother because she was not a fan. But somehow, even though being told repeatedly to the contrary, my aunt kept thinking she was. This totally worked out for me because I became enthralled with Kandinsky from a very early age, pouring over those books for hours on end, on the floor behind the living room wing-backed arm chair. Drinking in those glossy Kandinsky coffee-table books was very formative for me and touched me in a deep way.

What my mom would have rather had as a gift was a village with a train going around the base of the Christmas tree. This she finally bought for herself once all of us were grown up and gone. Nobody got a bigger kick out of it than her.

We made a lot of cut-out cookies for every occasion. I had birthday parties where we frosted cut-out valentine sugar cookies, and when I was in college, she cut out gingerbread cookies in the shape of ghosts that she frosted white and gave raisins for eyes; she made enough for me to share with my whole dorm hall for Halloween and they were a hit with everybody.

She used to decorate the big picture window of our small house for holidays, even though we were in a subdivision on a road with very little traffic so hardly anyone would see it. One year she made an enormous ten-foot ornate heart for the window that even got a large photo in the newspaper. We never did figure out who called in the tip to the newspaper.

One St. Patrick’s day, my mother had a big, lavish dinner party planned of all green food that got cancelled by a blizzard dumping 24 inches of snow. We had the event the next week anyway, and somehow she made the awkwardly monotone meal even more fun by being on the wrong day.

I went to U of M basketball games with her and my dad. They had seats so close in the huge amphitheater we could smell the sweat. I screamed my lungs out, and ate popcorn. My mom always wore a symphony of yellow and blue, and had a whole wardrobe of it appropriate for every Go Blue occasion.

She was extremely intuitive– she had incredible spiritual sense– but without that vocabulary, she used to just simply say, “A little birdie told me.” Her most oft repeated motto was, “If you don’t have anything good to say, don’t say anything.” I think that is rather enlightened.

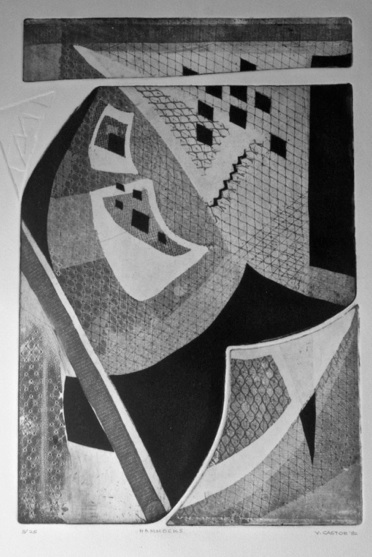

Her watercolors are vibrant and lovely. You can see some on this blog post. She did more representational work than abstract, but since I liked her abstract work better than anyone else, I ended up with more of it. She had an unrealized dream of getting a master’s degree in Printmaking, which I wish she had done. Below as well, you can see one of her intaglio prints; it is entitled “Hammocks.”

Sometimes my mom was in local art shows, but she rarely pursued them. The only painting from a show she ever sold she found out later her sister had surreptitiously bought; we watched her go from over the moon thrilled at the sale to offended. “I would have given it to her,” she exclaimed.

She did volunteer for many years in the U of M art museum as a docent, which placated a bit her longing for art and teaching. In her home, she always displayed her own artwork, which was constantly revolving in new configurations on the walls.

She had a bit of a silly rivalry with her older sister, who as a high-powered lawyer remained unmarried. Neither one allowed the other to help in their own kitchen, and each had to be waited on hand and foot as a guest in the other’s home.

We grew up on lots of bacon in the morning. Yesterday, when I asked my kids their first memory of my mother, “bacon” was the immediate answer. No wonder I ended up a bacon-eating vegetarian. She also made delicious homemade mac and cheese, a tad burnt at the edges, which were the best bits. A lot of people liked her meatloaf too. She’d make fancy food also that I didn’t like so well, such as scallops on the half-shell, or crown roast.

She called milk “moo juice,” and grape juice was dubbed “purple juice.” The puffy Cheetos were called “yum yums” and we indulged in them after school while debriefing in detail about our day. She was not a chocolate-lover, preferring fruity pastry, or desserts with custard or cloves or nutmeg or pumpkin. She raved over garlic-enhanced dishes in restaurants as well as salmon, but I could never get her to cook with either; somehow that was beyond her comfort zone.

She bought a package of Awrey date-filled cookies every week from the store. As the youngest, I shopped with her a lot. We’d go first to find the animal crackers, and I’d eat them sitting in the little basket in the cart while she shopped, chattering the whole time. When I asked what the feminine napkins were for, she told me they were mouse beds.

She washed and ironed for us a lot, and had a whole room for it in the basement. It makes me sad to think she probably spent more time there than anywhere. There was not a chore chart in our home. My mother worked hard so we could have a childhood. She said her mother had done that and she expected us to work hard so our children could have one too. But my children were responsible for doing their own laundry as soon as they were able, while still hopefully being able to “have a childhood.”

One summer day, my mother donated her wedding dress to our dress-up pile, and we have pictures of us as elementary school kids parading around in it, dragging it fraying on the patio and sidewalk, as we stumbled around with tiny feet in adult-sized high heels. There was nothing she had that she held back from us.

My mother got a speeding ticket as she naturally accelerated going down a huge hill outside of Peoria, Illinois, and I don’t think I’ve ever seen her angrier. She was hopping mad because she didn’t think it was fair to place speed traps where everyone would fall into them.

I made my mother a handmade glass bead necklace –yes, with a torch– that actually made it into a show at the American Craft Museum in New York City. Now, I reflect on how appropriate it is that my biggest claim to fine art fame was made for her.

She had gobs of necklaces and clip-on earrings. When I got my ears pierced at age 19, she said, “what are you going to do next, get a tattoo?” She thought pierced ears were barbaric. She enjoyed painting her nails with me, however, but she was never into any other makeup other than bold nail polish and rather garish lipstick which she could pull off well with her darker skin. She would tan as soon as the first March wind blew.

My mom was a reader of fiction, biography, and art books. Her favorite books were: John Adams by David McCullough, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee by Dee Brown, and Undaunted Courage by Stephen Ambrose. Also liking a family saga, she read a lot of James Mitchner, Belva Plain, and Nicolas Sparks.

When my husband came to Ann Arbor to meet my parents, he earnestly told them he wanted to marry me because “I’ve never met anyone like her before.” At this, they both burst out in uncontrollable laughter, my mother saying that was the understatement of the century. They understood better than he did what a non-conformist I was.

Soon she was asking his shirt size and writing down his favorite foods. Later, she said that it seemed to her like I was marrying someone so much like her; she couldn’t fathom that he too liked to sew and garden, would become a full-time dad, and take over the laundry. She made my husband promise never to let our children use coloring books. And then as a doting grandma, she framed my kid’s early scribbles.

There were visits with their grandkids, both here and there, but states apart, it did not happen often enough. Once she bought special cardboard clips and made a marvelous airplane together with my young kids in her backyard out of big appliance boxes. They played in it all day long and thought it was wonderful.

There was a framed card in my parents bedroom (in addition to a wall of photos of her three daughters at every stage) showing a young couple with one heart between them, and as the couple grows older they are surrounded by more and more hearts, until the last image depicts the elderly couple submerged in them. This seemed to sum up my parent’s long marriage well; it started out strong and got better and better.

My mother not only loved my father and ran his home, but did medical drawings for presentations he gave all over the world. She loved traveling with him, loved the discovery, the new places to see, and going out to new places to eat. I’m not really sure where she liked best, but I would guess it was either New Zealand or Hawaii. We have copious scrapbooks of her photos, all carefully glued down in non-archival rubber cement.

Anytime when she’d leave her home, she’d pat the table and say, “Goodbye, house.” This was heartbreaking when she did it the last time, never to return.

She used to say, “behind every great man there is a woman.” In the case of my father that was true. But this was a woman who was great in her own right too.

1 Comment

Pingbacks

-

[…] Reminiscences of my Mother […]