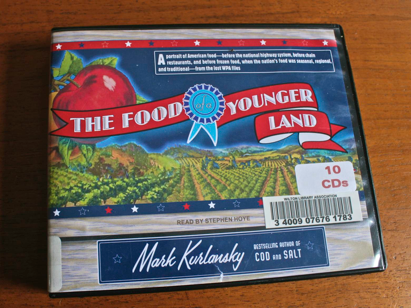

Mark Kurlansky has a definitely different take on food writing, more steeped in history and culture and macro-cosmic trend than most. Having enjoyed his two previous history-of-food titles, Salt and Cod, I was interested in seeing his views of 1930’s era food in this country,especially after reading recent experts repeatedly say, “We should eat as our grandmother did.”

After listening to this audio, I think we don’t want to eat as our grandmother did! Even if you put aside how much possum and squirrel and eyeballs were enthusiastically consumed (for my own grandmother it was frog legs) this diet was glutted with lard, sugar and deep frying. Maybe vegetables weren’t considered interesting enough for mention? For with the exception of popcorn, they are notably missing in this account.

This book is mostly a compilation of writers in the 1930’s who were working for FDR’s Federal Writer’s Project (FWP). The FWP was a public works project to nationally employ starving writers during the depression. They were paid a living wage to work for the government and this opportunity allowed them not only to eat, but to maintain their self respect and dignity. Their first project was to write local travel guides to each of the 50 states, a project that was completed and successful. After that, needing a new focus, they turned their attention to recording regional food. However, even though these writer’s turned in their writing, the FWP was dissolved before their work was ever published. Kurlansky has plumbed those archives for the best anthropological bits and vignettes, and shared them with us in this book, in the original writer’s own words and dialects. Among these original writers are even noteworthy famous ones like Zora Neale Hurston (see here) and Richard Wright.

Most interesting to me was that many of these writers back then when looking for fodder to write about, turned not only to their present day experiences, but interviewed their elders who told them about hunting buffalo, or learning to make pemmican from the Indians. They felt things were changing so much, yet from our perspective they were still very close to our pioneer and homesteading roots; refrigeration wasn’t even always present! Salmon were still so plentiful that you could cross the stream on their backs. How little could they imagine the massive changes the food business would sustain in the next fifty years!

In this volume, we hear about the culture of maple syruping in Vermont and the Automat phenomenon in New York City. We learn the history of the hoe cake and the clam. We join in at barbecues and chitlins feasts in the south, and on the stool of the Oyster bar in Grand Central (whose famous oyster stew has it’s recipe offered: it is made of mostly butter.) We work hard side by side with the competitive women preparing enormous company meals for their itinerant threshers, attempting to outdo what their neighbors will do for them…

There are recipes here interspersed with mostly prose, so if you actually want to cook any of these old fashioned recipes, you may prefer the print edition. (My brother-in-law has fond memories of “chess pie” and I always thought it would be fun to make him one, but not now that I know what’s in it! Some of these depression era recipes were born when they were hard up for any good ingredients!) Anyway, there were no recipes in this book that I’ll be trying, but if you want to dig a pit to bury two cows to slow cook under ground, there are detailed instructions! Often truth is stranger than fiction…

This was an interesting listen in the car for short, frequently interrupted driving bursts, as it is full of interesting bits of trivia you’d not be likely to learn otherwise, but it was dry enough that I’m not sure I would have gotten through it in print. (I give it three and a half stars.) If you ever wondered where we are headed with the national or global diet, this historical perspective will only underscore how quickly things can change! Please, let’s be part of a change for the better?