–

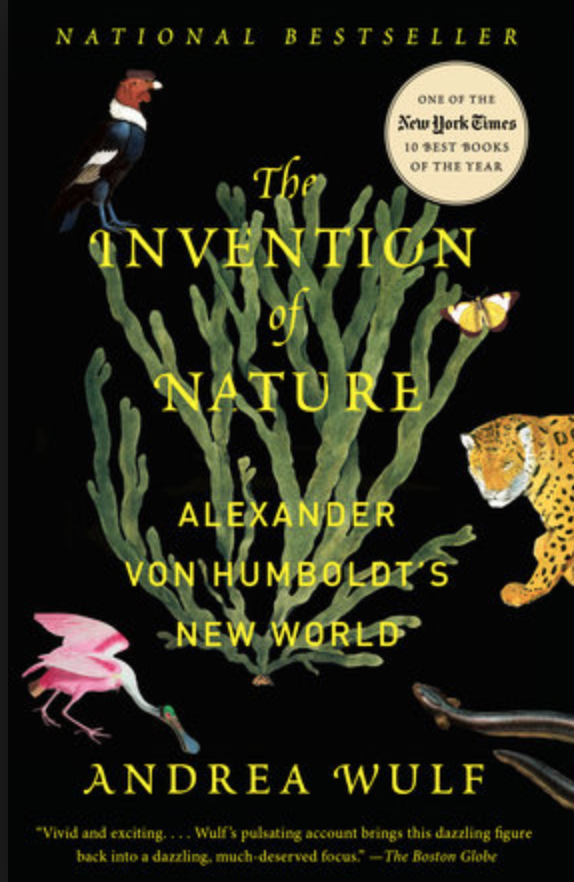

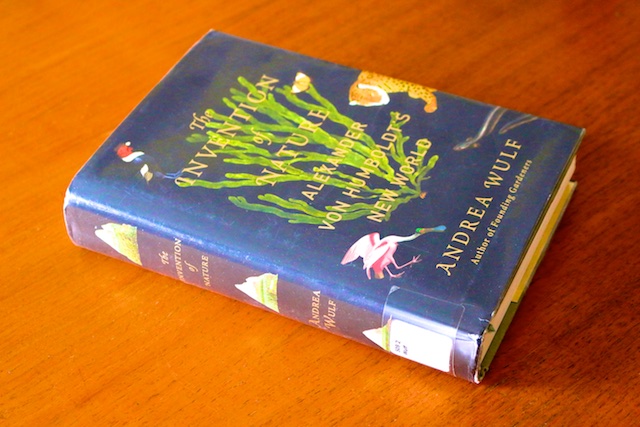

I really liked this biography about Alexander Von Humboldt, who was one on the most famous people in the world in the nineteenth century. More places and things on the globe are named after him than any other one single person. And I knew really nothing about him.

He was a guy before his time. He “combined scientific research with a warmth of feeling.” He was the first to understand the connectedness of all nature, and believing that it was a unified system. He spent his life proving that and writing widely about it. He saw “nature as a living whole instead of a dead aggregate.” He traveled to South America in the early 1800’s, climbing volcanos, and traveling down the Orinoco, stung by electric eels. He saw the devastating effects of both deforestation and monoculture all the way back then, and wrote against both, criticizing them harshly. He was against colonialism and slavery and was vocal about that too. He coined the term isotherms. He collected a huge quantity of data and samples to bring back to Europe for scientists to study. And he got a vast network of scientists to collaborate together on obtaining the details he published in his sweeping books that defended and explained nature. These works were factual but not antiseptic; they were passionate and poetic. He was awed and appreciative of creation, but also assembled and compared data assiduously as a scientist. Nature and art were closely related in his work, and he thought that whatever was against nature was unjust and bad. He felt we must not only be careful of nature, but be aware that it is a reflection of the condition of the whole. If nature is in trouble, so are we. He even went so far as to predict the devastation of human-induced climate change.

Humboldt had close friendships with many influential and talented people. He briefed Thomas Jefferson on Mexico and South America at a time when we had just obtained the Louisiana Purchase; he was our only source of information on that vast continent for many years. Humboldt was good friends with the famous writer Goethe, and was the inspiration for that author’s most famous character, Faust. Goethe said of Humboldt that he “lit science into a burning flame.” Humboldt was also friends with Simon Bolivar, before Bolivar lead the revolution to free South America from colonialism; he initially encouraged Bolivar, until Bolivar was successful. (Bolivar went on to disappoint Humboldt by becoming a dictator.) Humboldt inspired Charles Darwin to travel on the Beagle; he was Darwin’s role model and mentor, and Darwin knew all of Humboldt’s books by heart.

And Humboldt inspired others that he never met through his writing. Wordsworth read and commented about Humboldt’s work. Humboldt’s books inspired Jules Verne’s adventure novels. Edgar Allen Poe dedicated his book to Humboldt. Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman were enthusiastic readers of Humboldt’s work, which shaped their world views. Henry David Thoreau was also influenced deeply by Humboldt, so much so that he moved to Walden Pond to do similar type of scientific work (merged with poetic sensibilities) about all one small space, instead of Humboldt’s global perspective. Humboldt and Darwin both influenced March who wrote the first book on Ecology (called Man and Nature) about man’s devastating effect on nature and the need to be careful not to irreversibly injure our natural world. Then, in turn, Humboldt, March, and Thoreau, all influenced John Muir, who furthered the concept of protecting nature from blundering mankind.

Here’s a sample bit of this book’s prose: “Humboldt insisted that there were no superior or inferior races. No matter what nationality, color, or religion, all humans came from one root. Much like plant families, Humboldt explained, which adapted differently to their geographical and climatic conditions but nonetheless displayed the traits of a common type, so did all the members of the human race belong to one family. All men are equal, Humboldt said, and no race was above another, because ‘all are alike destined for freedom.’ Nature was Humboldt’s teacher. And the greatest lesson that nature taught was that of freedom. ‘Nature is the domain of liberty,’ Humboldt said, because nature’s balance was created by diversity which might in turn be taken as a blueprint for political and moral truth. Everything from the most unassuming moss or insect to elephants or towering oak trees, had its role, and together they made the whole. Humankind was just one small part. Nature itself was a republic of freedom.”

The book takes many twists and turns giving background not only into Humboldt’s life but also all these others as well who were either his friends or stood on his shoulders. At first these detours struck me as rambling until I saw how they all fit into pieces of a larger life. Then I started to enjoy them more. Humboldt’s life was not only extraordinary, but he encouraged and inspired so many others, that the power of it lay as much there as in anything he worked on so diligently himself.

I’m so glad I read this book and thank blog reader David for recommending it to me. Any of you history buffs or environmental enthusiasts out there would enjoy this too. This book is brilliantly researched, pragmatically told, and wildly relevant. I give it five stars.

–

5 Comments

-

Hi, Polly, I read this book in hardcover beginning in January 2016, just after the book had been named one of the best non-fiction books of the year by both The Economist and The New York Times. I too had never heard of Humboldt and was embarrassed given how well known he was, including in the U.S., in the 19th century. I found the entire book fascinating, including in the ways that you did. Now I am reading books by or about John Muir, Thoreau, and other naturalists or nature writers in the 19th century, as well as some in the 20th and 21st centuries, and I am always on the look-out for Humboldt’s name and for acknowledgement of his influence on so many people. After I read Wulf’s biography of Humboldt, I also read about Humboldt’s influence on Darwin in other sources. I think this book should be a must-read but it is very long! Thanks for the excellent review and for giving such rich examples from the book. Jane

-

Author

So glad to hear!

-

-

Wow! This sounds wonderful….thanks Polly.

-

Author

I think you’d like it.

-

Pingbacks

-

[…] A book about nature: The Invention of Nature: Alexander Von Humboldt’s New World by Andrea Wulf (my 5 star review here) […]